No time to tinker tinker tinker

I have long suspected that the operating system a person chooses functions as a kind of personality test. Show me your dotfiles and I will show you the architecture of your assumptions about how computers should behave.

tl;dr I am good, bro. Maybe I do have a life? But just look how long the post is!

I first wandered into NixOS territory back in 2020, spending over half a year with the system. The package collection impressed me then and impresses me now. The concept remained lodged in my mind like a splinter of possibility. Recently I decided to give it another chance as my daily driver, thinking perhaps the ecosystem had matured, perhaps the rough edges had been sanded down.

The pitch sounds absolutely seductive to a certain type of mind: define your entire system in a declarative configuration file, and the machine shall reproduce itself with perfect fidelity. Your laptop dies? No matter. Clone the config to new hardware and everything returns exactly as it was.

The promise whispers: reproducibility. The promise whispers: rollback your mistakes. The promise whispers: you shall never again lose your system to the chaos of accumulated cruft.

The promise, it turns out, contains some rather significant omissions.

Everchanging target and tinkgering tinker tinker tinker

Here is what I discovered during my time in the Nix monastery:

The system breaks. Not occasionally. Not rarely. Constantly. And surely your working machine is still fine but your configs to update your machine might be outdated. One does not simply run nixos-rebuild and proceed with one's day. One runs the rebuild, receives an error, adjusts the configuration, runs it again, receives a different error, adjusts again, runs again. The rebuild/fix/rebuild/fix cycle becomes the primary experience of using the system.

I have broken Arch Linux exactly once in five years. NixOS breaks before I even attempt an update. Something always requires changing in the configuration before the build will consent to run.

The error messages deserve special mention. They emerge from the machine like communiques from a dimension where clarity is considered impolite. Twenty lines of stack traces referencing files in /nix/store/ with names that look like someone rolled their face across a keyboard, and then at the very bottom, almost as an afterthought: "logseq has been removed."

The package you use daily? Gone. No alternative suggested. No migration path offered. Simply… removed due to lack of maintenance. As if the system itself had decided you needed practice in adapting to sudden loss.

Hard Things Easy, Easy Things Impossible

There is a saying about NixOS that circulates among those who have tried it: it makes hard things easy and easy things hard. This is, in my experience, precisely correct.

Want to define your entire system state in a version controlled file? NixOS handles this elegantly. Want to quickly install a package so you can get on with your actual work? Prepare to learn why your particular use case requires an overlay, or why the package exists but is marked broken, or why you need to add an additional input to your flake, or why the version you need conflicts with something else in your dependency tree.

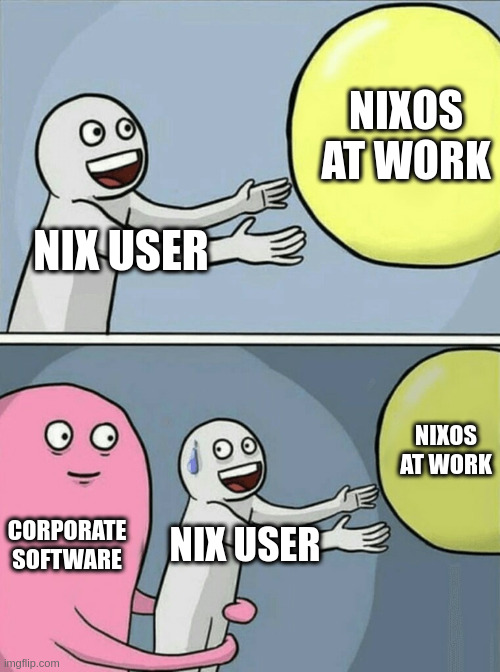

And then there are proprietary binaries. Corporate software. Anything not packaged for NixOS. This is where the immutable dream collides with the messy reality of software distribution.

On a traditional Linux distribution, you download a binary, make it executable, and run it. On NixOS, you enter a world of workarounds: steam-run, buildFHSUserEnv, patchelf, autoPatchelfHook, manually specifying interpreters and library paths. The StackExchange thread documenting these methods reads like a catalog of incantations, each with its own trade-offs and failure modes. Yes, this is the cost of running an immutable system. But when running a downloaded binary requires consulting documentation and selecting from multiple incompatible approaches, something has gone wrong with the user experience.

A computer, at the end of the day, should be a tool for getting work done. This seems obvious, yet NixOS has a way of inverting this relationship. The computer becomes the work. The configuration becomes the project. The tool demands more attention than the tasks you acquired the tool to accomplish.

My own dream was modest: atomic project directories with nix-shell, containing all dependencies, activated automatically when I enter the directory. I already use direnv quite effectively for this. The NixOS vision promised something even more sophisticated, a world where each project carries its complete environment specification, perfectly reproducible across machines and time.

The reality? When I start a new project, I want to get it running as soon as possible. I do not want to spend an afternoon figuring out how to declare dependencies in Nix. I do not want to debug broken overlays. I do not want to discover that some package I need will never be officially maintained because it fell on the wrong side of a political dispute within the community. (Xlibre, the Firefox fork, provides a useful example of how ideology can trump utility in package inclusion decisions.)

More and more of my actual work lives in Emacs or on the shell. Once a system is configured and running, I have little need to tinker with it. The operating system should fade into the background, a substrate upon which real work occurs. NixOS refuses to fade. It demands constant attention, constant maintenance, constant appeasement.

The Governance Situation, Or: When Your Package Manager Becomes A Political Battleground

Here is where the story becomes genuinely strange.

NixOS has developed what might charitably be called an "intense political culture." The project has been convulsed by governance disputes that make ordinary open source drama look quaint by comparison.

In April 2024, a faction proposed creating dedicated voting seats for specific demographic categories on a project committee. Some contributors suggested this might constitute discrimination against groups not granted such seats. The response was not a measured discussion of competing values. The response was what project leaders explicitly called a "purge." Contributors were banned. The founder, Eelco Dolstra, was pressured to sign an abdication letter that others had drafted for him.

Now, I want to be careful here. Reasonable people can disagree about representation policies. The question of how to make open source communities more welcoming admits multiple answers, and thoughtful people hold different views.

What seems less reasonable is labeling everyone who disagrees with your specific implementation a "Nazi" and removing them from the project. The word has a meaning. It refers to adherents of a specific ideology responsible for industrial genocide. Using it to describe someone who thinks committee seats should not be allocated by demographic category does not clarify anything. It obscures. It transforms a policy disagreement into an accusation of monstrous evil, which conveniently exempts one from having to engage with the actual arguments.

This rhetorical move, I should note, works equally well when deployed by any faction. Once you have established that your opponents are not merely wrong but wicked, any action against them becomes not just acceptable but morally required. The technique is old. It is effective. It does not produce good software or healthy communities.

The situation continued deteriorating into 2025. In September, five of seven moderators resigned, accusing the Steering Committee of interference. Or perhaps the Steering Committee was attempting to address problems with moderation bias. The accounts diverge depending on who you ask. LWN covered the fallout, and the commentary reveals just how deep the divisions run. What seems clear is that a Linux distribution has become a venue for political conflict that has little to do with package management, and the fallout is not producing better software.

The Paradox of the Immutable Dream

Here is what makes all of this so frustrating:

The idea of NixOS is genuinely excellent. An immutable, declarative operating system. Define your reality in a configuration file. Reproduce it anywhere. Roll back mistakes effortlessly. This is not foolish. This is, in fact, exactly what many of us want from our computers.

I should note: I love immutable, declarative systems in the right context. On the server side, systems like Talos and Bottlerocket Linux demonstrate the genuine value of this approach. When you need security, reproducibility, and minimal attack surface, declaring your system state and preventing runtime drift makes perfect sense. These systems work because servers have constrained, well defined purposes. You know in advance what the machine needs to do.

A personal workstation operates under different constraints. You do not always know what you will need tomorrow. A new project appears. A client requires some obscure tool. You want to experiment with a technology you read about this morning. The freedom to simply install something and proceed with your work has real value. NixOS trades this freedom for theoretical reproducibility, and the exchange rate is unfavorable for daily use.

The execution has problems. Significant, practical problems that make daily use a trial rather than a pleasure.

The political situation introduces additional uncertainty about the project's future direction and whether it can maintain the contributor base necessary for a healthy ecosystem.

And yet nothing quite like NixOS exists elsewhere. You can approximate its features: BTRFS snapshots for rollbacks, git repositories for dotfiles, aconfmgr for declarative package management, Docker for development environments. These solutions work. They do not require learning a pure functional configuration language or monitoring mailing lists for political developments.

But they are not the same thing. They are workarounds, not the integrated vision NixOS promises.

I find myself wishing for a project with NixOS's conceptual ambition, maintained by people capable of distinguishing between technical disagreements and moral emergencies, documented clearly enough that the Arch Wiki does not remain the superior reference for basic tasks. Something perhaps built on Gentoo's foundations, for those who appreciate that sort of thing, but with governance that prioritizes building software over enforcing orthodoxies.

Such a project does not appear to exist yet. Perhaps someone will fork the technology and rebuild the community on different foundations. Perhaps someone like DHH will stumble into this space and create enough noise to force a reckoning. Perhaps a new project will emerge that captures the declarative dream without the accompanying dysfunction as Ubuntu did back then with Debian.

Until that day, the NixOS concept remains in a peculiar limbo imho: too broken for daily use, too unique to ignore entirely, too politically fraught to recommend without extensive caveats. It is not ready for personal use. Perhaps it will be someday. Perhaps not. And I do have my doubts about companies really using it besides as a Homebrew alternative for a package manager on Mac OS.

The Return to Simplicity

So where does this leave me? Not necessarily back to Arch, though the Arch Wiki remains one of the finest pieces of technical documentation ever assembled (and, ironically, often explains NixOS tasks better than NixOS documentation does).

My time with NixOS taught several lessons again:

Reproducibility has value, but not at the cost of hours lost to rebuilds and debugging. Error messages should communicate what went wrong, not recite the internal state of a lazy evaluation engine. A community more interested in political purity than functional software will produce neither purity nor functional software. Sometimes the boring solution (Arch with BTRFS snapshots, version controlled dotfiles, containerized development environments) accomplishes most of the goal with a fraction of the friction.

What I actually want is simple: a configuration file that describes my system for easy setup. Something that installs my packages and applies my dotfiles when I set up a new machine. This should not be revolutionary. But there are already too many dotfile managers out there. This should not require learning a pure functional programming language. This should not force me to engage with political disputes about which software is ideologically acceptable.

Do I recommend NixOS? Not for daily use on a machine where you need to get work done. Do I recommend paying attention to NixOS? Absolutely. Something interesting is happening there, even if the interesting thing is primarily a demonstration of how technical projects can be consumed by non-technical conflicts.

The declarative, immutable operating system remains a worthy goal. The path to achieving it may require starting fresh, with different governance, different priorities, and perhaps a willingness to learn from NixOS's mistakes rather than repeating them.

Until then, there are distributions that simply work. There is the accumulated wisdom of decades of Unix documentation.